Monday. Vaguely religious-themed day. You guys get to be my diary for a bit. Could get personal, will be muddled, will probably contradict myself. You've been warned.

--------------------------------------------------------------

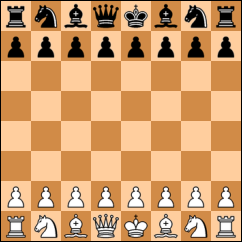

When I arrived at church yesterday I was greeted by a number of activites in the foyer, abrightly coloured parachute, a pool table, some giant jenga blocks, a game of twister and a large foam chess set. It was an all-ages service, something that our church does every now and then, and I look forward to them because 'all-ages' generally means 'for the kids', and that means that I can dance to the music without getting funny looks (because kids songs generally have actions), don't have to listen very hard to the sermon (if there is one), and can generally act up, just enjoying being in the company of my friends in a gentle and welcoming atmosphere of the church community. The service didn't disappoint, it had enough depth to it to be a nice reminder to me about the nature of prayer, allowing people to share with each other instead of just sitting back listening to a minister, while keeping the kids at least moderately interested. This is a difficult task which I've tried to achieve before with only limited success, as it's hard to gear something so that adults will still get something out of a service that is by neccesity built for and around young children, and the old rule about never working with children or animals is a rule for a very good reason.

But that's not what this post is about. No, as you may have guessed given that this is the Leaflocker and I am who I am, this is a post about the chess and the Christian attitude towards it and other games, and just a bit of a braindump in general. It's going to ramble a bit as there isn't really a plan and I've got a couple of different ideas that I'd like to play with, a little bit serious and a little bit tongue in cheek, and of course it'll come at things from a Christian perspective, so if you dislike poor prose or religious content, this is your first and final warning: go read Dinosaur Comics or something.

The board was set up underneath a poster that explained that

'Chess is like our Christian lives; it requires forward planning, respect of your fellow players and the ability to adapt to new challenges' (I meant to take down what it said exactly, but the sign had disappeared by the time I got back there after the service, so I must apologise if my quote is not spot-on). This is an example of a habit of religious people that I find incredibly irritating, the idea that the word 'Christian' in that sentence makes any difference, implying that those who aren't Christian can't plan for the future or respect others, and aren't equipped to deal with new challenges. It might be true that non-Christians don't come at problems the same way that we do (at least when we're coming at things the way we should), but the kind of attitude that supposes that the heathens are somehow lesser than we are must be avoided like the plague.

I'm certain that this isn't what was meant by this sign, that for whoever wrote it 'Christian life' and 'life' are seem like synonyms in a religious setting. The ability that some people are blessed with, to look at parts of everyday life and see what it can teach us about the nature of God and creation, is a beautiful and precious gift that I try to foster in myself, but I see a danger here, an extension of the 'us and them' mentality that only causes divides and breeds an isolationism and disconnect between Christians and the rest of the world, something that worries me whenever I see it.

But I also see another message in this simple sign, something that as a gamer paused me to stop and think on a topic that I've visited many times in the past and will undoubtedly visit again. The mere presence of the sign, the acknowledgement that a game needs some justification of its holiness to be in the church foyer, worries me. Why can't a game be there as something for people (players and kibitzers) to do together to pass the time before the service? Why does it have to be justified as something that builds us up and can teach us something about God? A pool table is just a pool table, a chess board is just a chess board, a medium for us to exercise or minds and our bodies, share with others just by being together? Maybe that's enough. But when we spend hours bent over a pool table or a chessboard, honing our skills and testing our mind alone, is that enough?

When I estimate the hours of my life spent playing or thinking about video games, for example, playing Pokemon, watching re-runs of Doctor Who, reading pulp science-fiction, things that have little or no positive effect on the world around me, it adds up a very large amount of time. Am I not only wasting that time, am I practising something that is inherently sinful? I've always settled on the position that as long as I don't set up these things as idols that distract me from the important things in my life, that they're acceptable, that they're beneficial even, to relax me, to occupy me, to improve my brain in some abstract and not easily defined way. Do I have to find something in every activity in my life that makes me more holy or helps myself or someone else in some little way for it to be justified?

It would be easier to just do as the Romans do, to justify things by saying "I am enjoying this, therefore I shall do it more", and trust that my God made me in such a way that I would only enjoy those things that are good for me, but that's a pretty cissy philosophy that doesn't gel with Christianity. I am fortunate enough to be part of a religion where there is a guidebook, albeit a few thousand years out of date, and it's pretty clear that doing as we wish isn't how we please God. So how do I find a middle-ground, where I can enjoy the little things, help bring joy to the lives of the people around me, and grow closer to God at the same time.

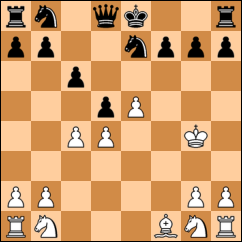

I don't know. I've never known. I try things, and they mostly don't work. But I know that I can't spend my life concerned only with Godly things or I'll go mad, and I know that I could easily spend my life playing games, but I'd be just as mad. I guess I just keep trying to spend as much time as I can bring myself to in the first category, pray for the strength and the wisdom to know the difference, and get as good at the French Defence as I can along the way.

But since I like to hedge my bets, here's a few tongue-in-cheek justifications for the way I seem to be spending my down-time at the moment:

'Chess is like life. It teaches us that those who move first have a slight advantage, that learning from the book isn't enough without real experience, and that sometimes a draw is the best outcome we can hope for.'

'Trumpeting is llike life. We'll only get better at it if we grow the calluses, and until then it's sometimes going to be terrible.'

'Chaturangaraja is like life. It teaches us the power of the King, not to neglect the little pieces, and that even the smallest actions can yield unexpected fruit.'

'Doctor Who is like life. There's always time to talk, the nice guys always win in the end, and that there's always another Dalek just around the corner.'

'Pokemon is like life. It teaches us to devote time to levelling up, even when it seems like a grind, to regularly check the guidebook for handy hints, to talk to everybody, and to always keep a stock of pokeballs. And you can always make it harder if you want a challenge.'

'Drinking tea is like life. It might be bitter, but the world be a less interesting place and conversations would be more awkward without it.'